If you are in the Los Angeles area -- or can get there before the end of the month -- it would be a terrible shame for you to miss the tea-related exhibit at the Fowler Museum at UCLA. The exhibit, 'STEEPED IN HISTORY: The Art of Tea', has been guest-curated by Beatrice Hohenegger, author of Liquid Jade: The Story of Tea from East to West, which has already been reviewed in CHA DAO. The book itself was a tough act to follow, but Hohenegger has certainly done it again with this latest achievement. Three years in the planning, STEEPED IN HISTORY brings together a number of rare, beautiful, and historically significant artefacts --

If you are in the Los Angeles area -- or can get there before the end of the month -- it would be a terrible shame for you to miss the tea-related exhibit at the Fowler Museum at UCLA. The exhibit, 'STEEPED IN HISTORY: The Art of Tea', has been guest-curated by Beatrice Hohenegger, author of Liquid Jade: The Story of Tea from East to West, which has already been reviewed in CHA DAO. The book itself was a tough act to follow, but Hohenegger has certainly done it again with this latest achievement. Three years in the planning, STEEPED IN HISTORY brings together a number of rare, beautiful, and historically significant artefacts --  across a remarkable spectrum of variety -- to illustrated the intricate, sometimes nigh-incredible history of tea-drinking on this planet.

across a remarkable spectrum of variety -- to illustrated the intricate, sometimes nigh-incredible history of tea-drinking on this planet.It would be difficult to imagine a more inviting exhibition space than that at the Fowler. Located on the north campus of UCLA, it both bespeaks the university's commitment to museum culture, and proffers a venue where town can mingle congenially with gown. A central courtyard, essentially a postmodern reinterpretation of the Renaissance Italian cortile di palazzo, offers seats by a fountain where one can periodically relax and take the sun, as an antidote to Stendhal Syndrome. The building that surrounds this has space for two large shows at any given time, plus a museum store.

STEEPED IN HISTORY begins as it absolutely ought to begin: with a table full of different types of actual tea. From the very first moments, the visitor can see dishes of dry leaf, of various sorts, from green to oolong to red/black to pu'er, and (if no one is looking) actually take a sniff of them. Against the glowing backdrop of the exhibit's poster, the table proclaims that everything that is to follow is for the sake of these wrinkled, dried leaves, and their human consumption. All the commerce, all the coercion and war, all the dreams and enjoyment and desire -- all of these motivations have flowed through millennia of human history for the sake of something we grow and prepare and drink.

STEEPED IN HISTORY begins as it absolutely ought to begin: with a table full of different types of actual tea. From the very first moments, the visitor can see dishes of dry leaf, of various sorts, from green to oolong to red/black to pu'er, and (if no one is looking) actually take a sniff of them. Against the glowing backdrop of the exhibit's poster, the table proclaims that everything that is to follow is for the sake of these wrinkled, dried leaves, and their human consumption. All the commerce, all the coercion and war, all the dreams and enjoyment and desire -- all of these motivations have flowed through millennia of human history for the sake of something we grow and prepare and drink.Hohenegger's arrangement of the exhibit is a triumph. Broadly historical in its strokes, it ranges across space and time, but also across the human arts and crafts -- ceramics, metallurgy, cabinetry, textiles, painting, sculpture, even architecture -- in order to illustrate how far-reaching has been the impact and the appreciation of tea.

A matrix organizing the material of this exhibit would have to be at least three-dimensional: chronological, cultural, categorical. And that would not even begin to organize the types of tea entailed, their methods of preparation and enjoyment, or the ways in which people have reacted to the need for tea (aesthetic, spiritual, dietetic, sociological, political). But all of this is represented in the several exhibition rooms of STEEPED IN TEA. Please join me now, gentle reader, for a virtual stroll through these rooms.

A matrix organizing the material of this exhibit would have to be at least three-dimensional: chronological, cultural, categorical. And that would not even begin to organize the types of tea entailed, their methods of preparation and enjoyment, or the ways in which people have reacted to the need for tea (aesthetic, spiritual, dietetic, sociological, political). But all of this is represented in the several exhibition rooms of STEEPED IN TEA. Please join me now, gentle reader, for a virtual stroll through these rooms.China, The Cradle of Tea Culture

As one leaves the antechamber, the exhibit turns its focus -- as of course it must -- with China. Even here, however, one feels the impact of cross-cultural sharing: a breathtaking portrait of 神農 Shen Nong, the mythical discoverer of tea, is actually not Chinese but Korean in provenance.

This portion of the exhibit collects a sumptuous selection of rare and ancient porcelain teaware, dating from the eighth to the thirteenth centuries; the exquisite Song-dynasty chawan, executed in Qingbai porcelain, is by itself worth the trip to the museum. A group of scrolls and watercolors in this room illustrates the commercialization of tea in China.

This portion of the exhibit collects a sumptuous selection of rare and ancient porcelain teaware, dating from the eighth to the thirteenth centuries; the exquisite Song-dynasty chawan, executed in Qingbai porcelain, is by itself worth the trip to the museum. A group of scrolls and watercolors in this room illustrates the commercialization of tea in China.The Way of Tea in Japan

This portion of the exhibit is dedicated to the great efflorescence of interest in tea during the Heian period in Japan (794-1185 CE).

Hohenegger has been very careful here both to demonstrate the far-reaching debt that Japanese tea culture owed to China's, and to honor the Japanese tradition in its own right. Artefacts in this section evince the particular delicate aesthetic of Japanese tea-related arts, and an entire tea-room (of the type designed for the traditional cha no yu) has been constructed inside the exhibit. Clean-lined, austere in its simplicity, serene in its uncluttered elegance, it represents the removal to another world where one can spend time contemplating a beautiful calligraphic scroll or a cunning tea bowl, enjoying the company of friends and bearing in mind that this exact moment will never come again.

Hohenegger has been very careful here both to demonstrate the far-reaching debt that Japanese tea culture owed to China's, and to honor the Japanese tradition in its own right. Artefacts in this section evince the particular delicate aesthetic of Japanese tea-related arts, and an entire tea-room (of the type designed for the traditional cha no yu) has been constructed inside the exhibit. Clean-lined, austere in its simplicity, serene in its uncluttered elegance, it represents the removal to another world where one can spend time contemplating a beautiful calligraphic scroll or a cunning tea bowl, enjoying the company of friends and bearing in mind that this exact moment will never come again.Tea Craze in the West

One could easily devote an entire show to Chinese and/or Japanese tea culture, but to do so would fail to tell the story that Hohenegger intends to tell here. The next unit of her exhibit ponders the ways in which tea culture began to 'go viral' in the seventeenth century, from Orient to Occident.

In some ways, the next section of the exhibit is the most variegated -- and virtuosic -- of the whole. In it Hohenegger has grouped a fine collection of ceramics, metal teaware, furniture, printed documents, and paintings, that together chart the exciting (and sometimes bewildering) progress of tea and tea-drinking from Asia to the western hemisphere, beginning in the Netherlands. The exhibit documents the way in which this orientalizing practice became, among other things, a status symbol for wealthy Europeans. In this section we find more eye-popping porcelain as well as sumptuous objects of teaware fashioned in precious metals.

In some ways, the next section of the exhibit is the most variegated -- and virtuosic -- of the whole. In it Hohenegger has grouped a fine collection of ceramics, metal teaware, furniture, printed documents, and paintings, that together chart the exciting (and sometimes bewildering) progress of tea and tea-drinking from Asia to the western hemisphere, beginning in the Netherlands. The exhibit documents the way in which this orientalizing practice became, among other things, a status symbol for wealthy Europeans. In this section we find more eye-popping porcelain as well as sumptuous objects of teaware fashioned in precious metals. The politics of tea also rears its head in this segment. Events like the Boston Tea Party used tea as a symbol of oppressive taxation;

what is not widely known is that there were other similar 'tea parties' in the same period, such as the so-called 'Annapolis Tea Party' of 1774. Hohenegger has succeeded in tracking down -- and obtaining for this exhibit -- a rare 1896 painting by Francis Blackwell Mayer, The Burning of the Peggy Stewart, that dramatizes this event.

what is not widely known is that there were other similar 'tea parties' in the same period, such as the so-called 'Annapolis Tea Party' of 1774. Hohenegger has succeeded in tracking down -- and obtaining for this exhibit -- a rare 1896 painting by Francis Blackwell Mayer, The Burning of the Peggy Stewart, that dramatizes this event. Another American-Revolution historical tidbit that relatively few seem to know is that Paul Revere, he of the famed midnight ride, was a very skilled silversmith. STEEPED IN TEA includes a fluted silver sugar urn by Revere that I found mesmerizing -- as much for its beauty as for the hands that wrought it.

Tea and Empire

The final movement in this symphony of tea culture is at least partly in an elegiac key.

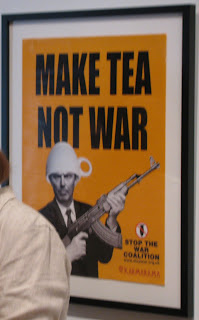

The story of 'tea and empire' is a sad one, including as it does the tragic history of the opium trade, and the massive numbers of Chinese who were enslaved to this addiction -- by a Britain hungry for more tea. This is the place where the tale of India comes into its own. 'Tea and Empire' includes more teaware, of course, but also an intriguing collection of posters, prints, photographs, and maps that make the sobering point about tea as a fulcrum of imperial power. Hohenegger is, however, unwilling to let the visitor depart without a smile on his face: One of the last items one encounters is a poster with the caption MAKE TEA, NOT WAR. A serious message with a light touch.

What makes STEEPED IN HISTORY such a pleasure to experience is its all-too-rare combination of meticulous scholarship with an acutely human appreciation of the beautiful and the enjoyable. Hohenegger, a trained historian, understands the need for factual accuracy, but -- and she shares this trait with all great historians -- that goal never eclipses or derails her sense of the lovely, the moving, or even the humorous. These vibrant traits shape and inform the entire exhibition. It is expansive but not exhausting; copious without being cramped or fussy. The physical progress of the walk through the exhibition space flows naturally and invitingly. And the depth of its interest is such that, upon completion of an entire viewing, one wants to go through the whole thing again. I do not know if it will be feasible for the exhibit, or some form of it, to travel to other museums after this show closes; but any museum looking for unusual and worthwhile material would do well to host it.

Beatrice Hohenegger is to be congratulated for a magnificent achievement in this exhibit. The Fowler itself is to be blessed for the care it has devoted to presenting the show in jewel-like fashion, but without preciosity or the slightest hint of kitsch. I myself would like to extend thanks both to Beatrice and to Stacey Ravel Abarbanel, Director of Marketing and Communications at the Fowler, for the warm welcome they extended me when I came to view the exhibit, and for their generosity in furnishing information and some of the illustrations in this essay. All images here are either used by their permission, or created by myself.

Outdoor poster for the exhibit. These were hung not only across campus, but on street lights in Los Angeles.

Outdoor poster for the exhibit. These were hung not only across campus, but on street lights in Los Angeles. 'Picking the Tea' (From a set of Twelve Studies of Tea Production) China, circa 1805. Gouache on paper. © 2009 by The Kelton Foundation.

'Picking the Tea' (From a set of Twelve Studies of Tea Production) China, circa 1805. Gouache on paper. © 2009 by The Kelton Foundation. Tea chest. Japan, early 20th century. Wood, exterior paper decoration, tin lining. Private Collection.

Tea chest. Japan, early 20th century. Wood, exterior paper decoration, tin lining. Private Collection. Tea bowl, Kyoto-Ninsei School. Japan, late 19th–20th century. Ceramic, glaze. Collection of Robert W. Moore.

Tea bowl, Kyoto-Ninsei School. Japan, late 19th–20th century. Ceramic, glaze. Collection of Robert W. Moore. Artist unknown, possibly Richard Collins (England, d. 1732). Man and Child Drinking Tea, circa 1720. Oil on canvas. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Artist unknown, possibly Richard Collins (England, d. 1732). Man and Child Drinking Tea, circa 1720. Oil on canvas. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.  The Middle Clipper Ship Derby in Hong Kong Harbor. China, circa 1860. Oil on canvas. Peabody Essex Museum.

The Middle Clipper Ship Derby in Hong Kong Harbor. China, circa 1860. Oil on canvas. Peabody Essex Museum. Detail of the Japanese tea room, showing the equipage used for the cha no yu.

Detail of the Japanese tea room, showing the equipage used for the cha no yu.

2 comments:

It sounds like a brilliantly curated exhibit. Your thorough description and wonderful choice of photographs are, at least, a bit of a vicarious glimpse into the show. Thank you.

I love the old silver teaware. That's what I collect--not antiques but just classic pieces to use every day. Next on my list is a sterling liquor flask I can put some strong Puerh in to take to town with me.

Post a Comment